L10-06, 10th Floor, Vincom Center, 72 Le Thanh Ton, Ben Nghe Ward, District 1

January 29, 2025

January 29, 2025

Dung Hoang Nguyen has over 22 years of experience in advisory, audit, appraisal, and M&A. He trained with Deloitte and KPMG before joining Kreston (VN) in 2008, becoming a partner in 2010. Dung is passionate about business growth and understands business life cycles from creation to exit. He advises numerous large national and international clients, leveraging his extensive experience. Dung has been a member of the Vietnam Association of Certified Public Accountants since 2007, the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants since 2015, and the Hanoi Bar Association since 2016.

August 2, 2024

Vietnam’s business environment is becoming increasingly open and supportive. Since 2014, the government has focused on improving the business climate through consistent reforms.

However, doing business in Vietnam comes with challenges. “Corruption and bureaucracy remain significant hurdles,” says Dung Nguyen Hoang, Partner at Kreston VN. Legal uncertainties and weak enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) also pose difficulties. Additionally, businesses face issues with inadequate infrastructure, skill shortages, and language barriers, often needing interpreters and translators.

Vietnamese exporters face specific challenges in accessing international markets. Dung highlights several issues: “Market development, intellectual property protection, financial constraints, competitive pricing, and language and cultural differences are major concerns.” Other challenges include compliance with market access regulations, logistics, quality standards, and trade barriers.

Access to growth finance is another obstacle for Vietnam’s companies. “The banking loan market is the primary source of credit, but over 50% of businesses struggle to secure funding,” says Dung. Many companies do not meet the credit requirements of commercial banks and lack long-term credit relationships.

Despite these challenges, the Vietnamese government’s ongoing reforms are creating a more favourable business environment. Addressing the existing issues will be key to ensuring sustained economic growth and greater international integration.

If you would like to speak to an expert in Vietnam, please get in touch.

April 11, 2024

Please visit the Kreston NNC Vietnam Tax guide page for advice on setting up businesses in Vietnam.

April 19, 2023

April 17, 2023

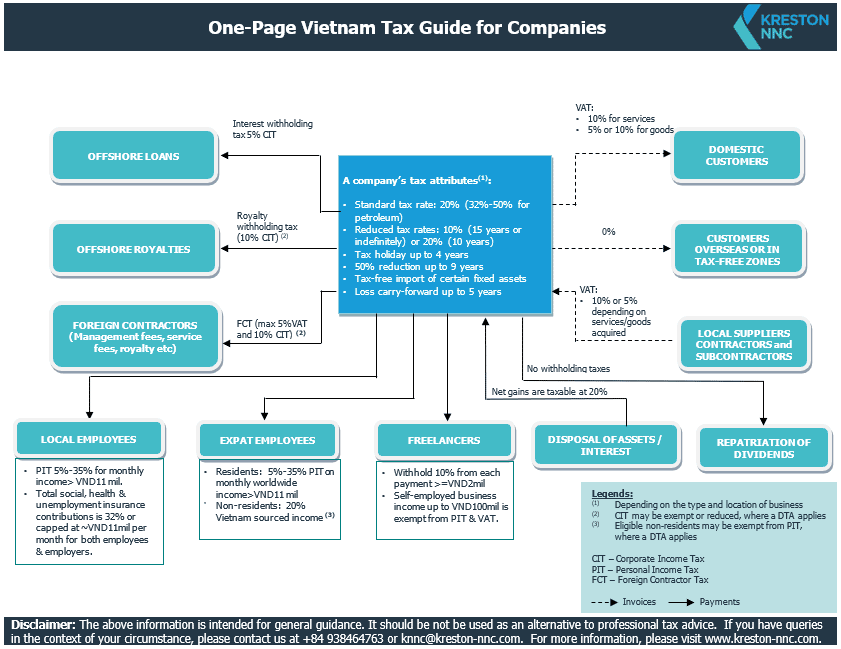

One-Page Vietnam Tax Guide for Companies

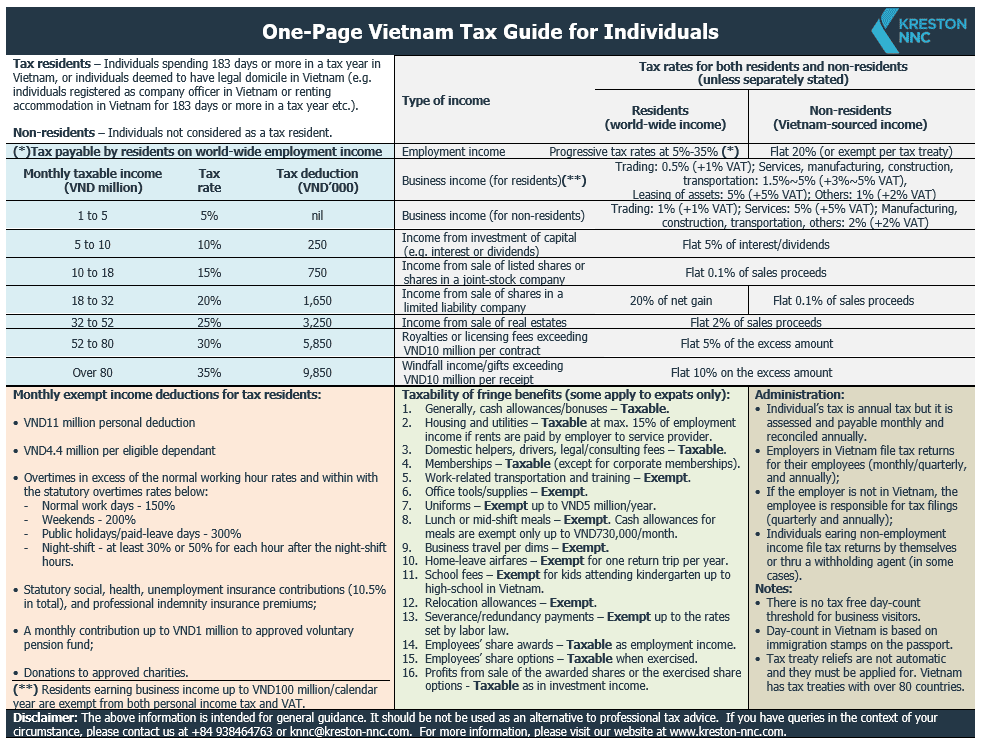

One-Page Vietnam Tax Guide for Individuals

December 15, 2021

Kreston Global tax expert, Nam Nguyen from Kreston NNC in Ho Chi Minh City, recently shared his experience of working with foreign investors in Vietnam with STEP Journal and how personal tax planning and understanding tax residence can save clients money.

What is the issue?

Vietnam taxes residents on worldwide income and non-residents on Vietnam-sourced

income, regardless of where they get paid.

What does it mean for me?

Tax rates for tax residents are comparatively high, with a 35 per cent top marginal rate and few tax reliefs.

What can I take away?

Personal tax planning is essential when advising clients considering working or doing business in Vietnam.

October 4, 2021

By Nam Nguyen, Kreston NNC, Vietnam

This week VN Express International reports that the Asian Development Bank has reduced its forecast of Vietnam’s GDP growth in 2021 to 3.8%. The World Bank has reduced it to 4.8% but forecasted a 6.5% growth next year, while the country targets a growth of 3.5-4%, after a 2.9% growth last year. The government in Vietnam has made announcements to allow resumption of most activities in Covid-hit cities and provinces from 1 October 2021, including Ho Chi Minh City, the commercial hub of Vietnam.

While Covid is still lingering in Vietnam and many other countries, proper cashflow management is important to affected businesses. International investors may be looking at different scenarios. Some may consider funding its Vietnam subsidiary to help it cope with cashflow difficulties. Others may consider scenarios such as mobilising idle working capital or retained earning from their Vietnam subsidiary to help their business elsewhere, suspension of the Vietnam subsidiary’s business, or even an exit option etc. While it is hoped that investors do not have to consider the last two scenarios, this article helps readers to familiarise themselves with the regulatory requirements and tax implications all mentioned scenarios.

Funding a Vietnam subsidiary

A foreign investor may fund its Vietnam subsidiary by increasing the charter capital (i.e. equity), providing a loan capital (i.e. debt), or simply providing a grant, or allowing a debt waiver. Increasing the charter capital requires pre-approval by the licensing authority and it is appropriate if the increased capital will stay in Vietnam indefinitely. There will be no tax implication or benefit.

Providing loan capital to a Vietnam subsidiary by way of a shareholder’s loan offers flexibility and tax efficiency. A shareholder’s loan may be capitalised to become an addition to the charter capital at any time. A foreign loan does not require the licensing authority’s pre-approval unless the loan will cause the Vietnam subsidiary’s total investment capital (i.e. equity plus debts) to exceed the licensed total investment capital. A foreign loan requires pre-approval by the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) if the loan period exceeds 12 months. However, a short-term loan (i.e. up to 12 months) does not require SBV’s pre-approval unless the loan period is extended beyond 12 months. A foreign shareholder’s loan may be repaid at any time, and hence, it may be used as a tool for future fund repatriation.

A lending foreign shareholder may charge an interest expense on the loan. The interest rate may be up to 150% of the local prime interest rate (subject to the usual rules on thin capitalisation, related party transactions, and transfer pricing). The interest payable to the lending shareholder by the Vietnam subsidiary will be subject to a 5% interest withholding tax but the interest expense will be tax deductible to the Vietnam subsidiary. For example, assuming that the Vietnam subsidiary is making taxable profits and is paying corporate income tax at the standard tax rate of 20%, then for every dollar of interest that the Vietnam subsidiary pays its oversea lending shareholder, it will pay 5 cents of interest withholding tax and get 15 cents of tax deduction benefit (i.e. 20% – 5%). In fact, this is one of the attractive features of Vietnam’s tax system that international investors may not be aware of.

What if the Vietnam subsidiary is not making any taxable profits to utilise the interest expense tax deduction? Such interest expense may be accounted for as part of the accumulated tax losses, which may be carried forward up to 5 years from the loss-making year.

A grant or debt waiver will trigger corporate income tax liability to the Vietnam subsidiary as they will be considered as the subsidiary’s taxable income. There will be no VAT implication unless the grant or the debt waiver is exchanged for goods or services to be supplied by the Vietnam subsidiary.

Other scenarios

Other scenarios include (i) the sale of the Vietnam business, (ii) the reduction of its charter capital, or (ii) business suspension. Both scenarios (i) and (ii) requires pre-approval by the licensing authority. Scenario (i) may trigger tax on capital gain. Scenarios (ii) and (iii) have no tax implication. The regulatory compliance paperwork process for scenario (i) is simpler and less time-consuming than scenario (ii). Scenario (iii) is simplest and requires only a written notice to the licensing and tax authorities. A company may apply for suspension or early resumption of business at any time. Previously, a company was allowed to apply for business suspension only twice. However, the current regulation no longer limits the number of times that a company may apply for business suspension. If a company has tax incentives (e.g. tax holiday or a 50% tax reduction period), then the unutilised tax incentives may be preserved only if the business is suspended during its pre-operating period.

Employees’ statutory redundancy payment may be another important consideration for companies with a large workforce. The labour law requires that if an employee is made redundant, the employer must pay a redundancy payment at the minimum of 2-month salary or one-month salary for every year of service to employees who have been employed for at least one year.

For a related guide on methods of repatriation of fund from Vietnam, please click here to view. The author can be contacted at nam@kreston-nnc.com

September 27, 2021

Nam Nguyen, Kreston NNC, Vietnam

The recently introduced taxation of e-commerce in Vietnam has triggered a series of issues. Beside those mentioned in the last two articles on this topic, below are others.

The key trigger is permanent establishment (“PE” i.e., taxable presence in Vietnam). As mentioned in the last two articles on this topic, digital presence may be deemed by tax authorities in Vietnam as physical presence for taxation purposes, especially for e-commerce businesses. Otherwise, it would defeat the purpose of e-commerce taxation, as Vietnam has effective tax treaties with around 80 countries, and many companies doing business in Vietnam are from these countries.

If PE is triggered, it means that foreign companies that have transactions in Vietnam may not be able to rely on a tax treaty to protect the business profits derived through a PE in Vietnam from Vietnamese taxation. Where a tax treaty applies, the PE definition of the relevant tax treaty will prevail. However, when a dispute with the tax authority in Vietnam over PE issues arises, it is often like an uphill battle for taxpayers. Where a tax treaty is not available, a foreign company doing business in Vietnam is even more vulnerable to Vietnam’s taxation if a PE arises, as PE is broadly defined under Vietnam’s domestic tax law. It includes (amongst other things) “an agent delivering goods or services in Vietnam on behalf of its overseas principal.”

When PE is triggered, the business profits of a foreign company are not protected from Vietnamese taxation, and there may also be the following potential tax implications.

1. Potential VAT implication

For example, a foreign company makes consumer products such as mobile phones or fashion apparel in Vietnam through an export-manufacturing arrangement with a manufacturer in Vietnam, and the company also sells its products online directly to Vietnamese consumers through its website or other e-commerce platforms. Normally, the export-manufacturing fees charged by the local manufacturer enjoy 0% VAT for export-manufacturing services, so the foreign company does not suffer a 10% VAT which would otherwise be charged by a service provider in Vietnam.

However, according to Vietnam’s current VAT regulation, if the services are rendered under a contract between a Vietnamese service provider and PE in Vietnam of a foreign company, then the 0% VAT rate will only apply if the services are performed outside of Vietnam. In export-manufacturing, the services are obviously performed in Vietnam, so the manufacturing fees will be taxable at 10% VAT, if the foreign company is found to have a PE in Vietnam.

2. Potential foreign contractor tax implication

Another example is where a service is provided by a foreign contractor, to a Vietnamese customer, and it is performed outside Vietnam (known as offshore service). Such service may be exempt from the foreign contractor withholding tax (including 5% VAT and 5% corporate income tax), if it is “consumed” outside Vietnam, and if the foreign contractor does not have a PE in Vietnam. As an illustration, a foreign company provides conventional (i.e., offline rather than online) advertising or marketing services to a Vietnamese customer, to promote made-in-Vietnam products (whether they are made by a foreign owned company or a local company) in international markets, and the services are performed outside Vietnam. These services are exempt from the foreign contractor withholding tax. However, if they are provided as online services then they will be taxable, and so will it be the case if the foreign contractor has a PE in Vietnam.

3. Potential personal income tax implication

For business visitors to Vietnam who spend less than the aggregate of 183 days in Vietnam in a tax year, they are considered as non-residents, and they may apply for tax protection under a tax treaty. Most tax treaties with Vietnam provide that if the person’s remuneration is not borne by a PE in Vietnam then the person’s employment income will not be taxable in Vietnam.

However, in the case scenario (1) above, if the foreign company has a Representative Office in Vietnam which employs (just pays for the cost of) a non-resident expatriate executive (e.g., a regional procurement manager) who frequently visits Vietnam to conclude contracts with the company’s contract manufacturers. The Representative Office itself does not constitute a PE in Vietnam under Vietnam’s current tax regulation. However, if the company is found to have a PE, either under the case scenario (1) above because of its e-commerce activities in Vietnam, or because of certain activities undertaken by the Representative Office or by the non-resident executive, then the person may not be protected by the relevant tax treaty.

A foreign company may be found to have a PE in Vietnam in different ways and it may have more than one PEs in Vietnam. Vietnam’s current tax legislation is silent as to whether if a business is found to have a PE in Vietnam, then above tax treatments will only apply to the transactions associated with such a PE, or they will apply to all transactions. So, the risk of the latter exists, even if a transaction is not associated with the PE.

4. Potentially higher tax implication to PEs

Normally, if a PE is found then only the business profits derived from such a PE (if any) is taxable in Vietnam. However, under the current tax administration rules, Vietnam taxes the business profits of a foreign company that are derived through a PE in Vietnam primarily through the withholding tax regime, whereby a PE’s tax liability is based the contract value (i.e., revenue), instead of profits. For example, a PE is taxed at 1% corporate income tax and 1% VAT on of its trading revenue, or 5% corporate come tax and 5% VAT on its service revenue etc.

However, the foreign contractor tax regulation allows a foreign contractor to select the option of paying corporate income tax at 20% of profits (i.e., revenue – expenses), subject to successful tax registration as if the PE were an ordinary registered business in Vietnam. It means that the tax office may attempt to tax a PE at 20% corporate income tax on profits, instead of at a lower rate (1% or 5%) on the revenue. In this case, the tax on the business profits derived through the PE may be higher than 20% of the real business profits, because chances are that the foreign company may not be able to substantiate all its overseas expenditures (e.g., administration or management expenses) allocated to the PE for tax deductions. Vietnam has very strict rules on expense substantiation for tax deductions, and the tax regulation limits a foreign company’s allocation of management expenses to its PE in Vietnam by prorating the total global management expenses of the foreign company at the ratio of the revenue of the PE in Vietnam over the global revenue (including revenue of all PEs in all countries).

However, the tax regulation also states that no tax deduction is permissible where a PE in Vietnam does not maintain adequate bookkeeping according to Vietnamese accounting standards, which may be the case for a foreign company that is found to have a PE in Vietnam by accident.

Therefore, international businesses that intend to further penetrate Vietnam’s market through e-commerce should be mindful of the higher PE risk, and the above potential additional tax implications.

If you have missed the last two articles on this topic and would like to read them, you may click here to view the first article and click here to view the second article. The author can be contacted at nam@kreston-nnc.com.

September 2, 2021

By Nam Nguyen, Kreston NNC, Vietnam

Vietnam’s recent introduction of the taxation of e-commerce may be a game-changer and worthy of a rethink of market entry strategies for foreign trading companies. Below is why.

In the past, the key considerations for foreign trading companies in deciding how to sell their products in Vietnam’s market, beside the need to test the market first, included the administrative challenges in setting up a trading company, due to Vietnam’s restrictions on wholly foreign-owned trading, distribution, and retail businesses. Obtaining the licenses to conduct direct import, trading, distribution, and retail involved a lengthy and costly process. Setting up a company in Vietnam required physical presence including a proper business premise, the exorbitant rental of an office space, and of course the consideration of whether the business was ready yet to establish a taxable presence in Vietnam.

Those considerations often lead foreign trading companies to the choice of selling their products to Vietnam under a distributorship agreement with a local distributor or through direct online sales, rather than setting up a subsidiary in Vietnam. These business models do not require any business license, save operating costs, have limited risk, and avoid taxable presence in Vietnam. In most cases, sales of products to Vietnam through a distributor or direct online sales were regarded as purely commercial transactions (or trading-WITH-Vietnam) and foreign suppliers were often not subject to the foreign contractor withholding tax. In the worst-case scenario, if a sale was regarded as a taxable transaction (or trading-in-Vietnam) the gross sales would be taxable at the deemed flat rates of 1% VAT and 1% CIT (corporate income tax). However, a foreign supplier could effectively pay no Vietnamese tax if it passed the VAT to its distributors or business customers (as they would be able to recover the VAT as their input VAT), and it could rely on a tax treaty with Vietnam (if applicable) to claim an exemption of the 1% CIT under the tax treaty. The risk of taxable presence (i.e. permanent establishment or PE) in Vietnam existed, but it was relatively lower than it is today.

The recent introduction of new rules on taxation of e-commerce potentially leads to increased PE risk in Vietnam for foreign suppliers. Although the issue has not yet been specifically addressed by the new rules, if digital business presence means physical business presence in Vietnam, then it would follow that foreign e-commerce suppliers could no longer benefit the trading-WITH-Vietnam exemption or tax treaty exemption. So, PE risk may no longer be relevant.

For trading sector, the profit margin is often low in comparison to other sectors, and volume is very important. As sales volume grows, paying CIT at 20% of profit (for trading companies) could be more tax efficient than paying a total withholding tax at 2% of the gross revenue. As an example, assuming the average gross margin for trading of popular consumer products in Vietnam ranges from 15% to 22% (or net profit margin from 4% to 8%, according to a private bench-marking exercise), then paying Vietnam’s withholding tax at a total of 2% on the gross sale revenue could be higher than paying the CIT at 20% of the net profit. If that is the case, then doing business in Vietnam as a foreign contractor may no longer necessarily be the most effective option for foreign trading companies.

It is needless to say that there are lots of advantages in trading in Vietnam through a local subsidiary than as a foreign contractor, which can give trading businesses a competitive edge. The advantages include greater market access, visibility and product marketability, efficiency, volume growth potential, and less dependency on local distributors etc. Besides that, setting up a trading company in Vietnam is much easier, faster, and less costly nowadays than it used to be. Therefore, it may be worthwhile of a revisit to this option.

Beside the company option, there is another option of setting up a Representative Office in Vietnam which can help a foreign trading company to achieve greater market access and visibility and drive volume growth in Vietnam. It is a hybrid option between the company model and the foreign contractor model. A detailed comparison of these three business models can be viewed here. If you missed our last article on this topic, please click here to view.

Kreston NNC’s team in Vietnam has extensive hands-on experience in helping clients reviewing and evaluating their Vietnam business models and market entry strategies. If you need professional support in this area, please contact the author at nam@kreston-nnc.com.

August 5, 2021

By Nam Nguyen – Kreston NNC, Vietnam

According to Vietnam E-commerce Association (VECOM)’s 2021 report, the average annual growth of Vietnam’s e-commerce sector is 30%, with USD13.2 billion revenue in 2020 and it is expected to reach USD52 billion in 2025. Last year, online retail sales increased by 46%, ride-hailing and food deliveries increased by 34%, online marketing & entertainment increased by 18%, and parcel deliveries increased by 47%. On average, there are 3.5 million online transactions per day, 80% of which are cash-on-delivery transactions.

Understandably, tax authorities in Vietnam are stepping up measures to claim their shares of tax collection in this fast-growing sector. They have been introducing rules targeting various stakeholders including local and international e-commerce suppliers, digital service providers and e-platform operators. The new rules require local banks, payment intermediaries, and consumers to assist the tax authorities by withholding taxes, filing tax returns, and paying taxes on behalf of targeted taxpayers, or identifying and reporting delinquent taxpayers.

So, whether you are a supplier, intermediary service provider, or consumer, it is important to know the new rules and be prepared before the tax authorities might come after you or your business.

This article looks at what may be required of you, or your business, whether as a seller, a buyer, or an intermediary.

The rules

Prior to 1 July 2020 (ie before the introduction of the rules on taxation of e-commerce), the key taxation rules already existed, but they were not expressly directed to e-commerce transactions. In essence, unless a business had already been registered for taxation (which is often the case of most local businesses) foreign suppliers or service providers (commonly known as “foreign contractors”) who had transactions with customers in Vietnam were required to pay a tax, foreign contractor tax, through withholding by their customers in Vietnam.

However, there was no obligation imposed on intermediary service providers such as banks, payment service providers, logistics providers, and customers who acquired goods or services for personal use. In practice, there were requirements that when acquiring goods or services from a foreign supplier, a business (rather than individual) customer in Vietnam was required to withhold the foreign contractor tax, file a tax return, and remit the taxes withheld to the tax office on behalf of the foreign supplier. Individuals doing business by supplying goods or services were also required to register for taxation and pay the applicable taxes, including VAT and personal income tax (PIT), on their business income. The rules are as follows:

In both cases, the tax rates are flat rates which are applied directly to the turnover. In the second case, if the goods title passes outside Vietnam, then it is regarded as a “trading-WITH-Vietnam” transaction which is exempt from foreign contractor tax, as opposed to a “trading-IN-Vietnam” transaction which is taxable. Cash-on-delivery transactions and the supply of goods that includes services (other than warranty) are obviously trading-In-Vietnam. For some services, if they are performed and consumed outside of Vietnam, they may be exempt from the foreign contractor tax. However, it is currently unclear whether these exemptions will continue to apply to e-commerce transactions.

Also, technically a foreign supplier may apply for tax treaty exemption of the 1% CIT where a tax treaty applies and if the supplier does not have a permanent establishment (or taxable presence) in Vietnam. It is also unclear whether the same rule will apply to foreign e-commerce suppliers, given that there are many uncertainties surrounding permanent establishment issues. For example, whether digital business presence is equal to physical business presence in Vietnam etc. As for VAT, if import VAT is already paid when the goods are imported, then the 1% VAT is technically exempt.

Effective 1 July 2020, the rules are summarised as below:

So far, this new e-commerce tax administration mechanism appears not to target logistics providers. However, given that 80% of e-commerce transactions in Vietnam are currently on cash-on-delivery terms, it would not be a surprise if the tax authorities introduce further rules that may require logistics providers (and other intermediaries, if any) to do the same.

Practical tax planning tips for foreign suppliers:

Tax planning tips for local buyers:

For local buyers, the following questions should be checked and cleared:

As the rules are new, it is likely there will be different interpretations that could lead to practical issues. Kreston NNC’s tax professionals are at the forefront of this new area of taxation in Vietnam. Our team has extensive hand-on experience in helping clients, ranging from start-up businesses to large corporations in Vietnam. If your business needs professional support in this area, please contact us at + 84938464763 or nam@namnguyenconsulting.com.

July 8, 2021

June 22, 2021