Practical Application of the Arm’s Length Principle in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

May 14, 2021

Practical application of the arm’s length principle in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic

By Carlos D’Arrigo, Transfer Pricing and Valuation Partner, Kreston BDM

In 2021 most taxpayers around the world would face an unprecedented challenge to reflect how their 2020 transactions compared to fair and open market values simply because in a crisis downturn like no other with disruptions and restrictions across almost every industry, how can you define what market conditions were fair? In the so-called phrase “business as usual”, how can you explain “usual”? We are not quite certain either but let’s try to find some answers.

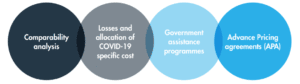

On December 18, 2020, the 137 members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (“OECD”) Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Action Plan (“BEPS”) released the Guidance on the transfer pricing implications of the COVID-19 pandemic (the “Guidance”) with the purpose of helping both taxpayers and tax administrations in reporting the financial periods affected by the pandemic in compliance with the arm’s length principle[1]. The guidance provides insights for the following four priority issues:

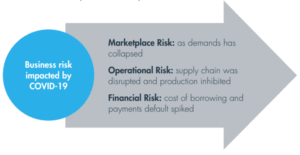

The Guidance recommends to first identify each specific cause that impacted taxpayers results and group them into three risk bubbles: Market Risk, Operational Risk and Financial Risk. The following chart intends to show a more comprehensive process flow:

Identify specific cause

• Drop in sales volume and/or price

• Increase in material and labour cost

• Increase in overhead expenses

• Exceptional, non-recurring, extraordinary operational cost

• Decrease in capacity utilisation or economy of scale

• Increase in days inventory and obsolescence

• Increase in days Receivable

• Increase in interest rates and bank fee charges

Once specific causes are identified, the Guidance suggests addressing each of them on a case by case basis using the following sources of contemporaneous information to support the performance of a comparability analysis applicable for Fiscal 2020:

Guidance suggested source |

Our comments |

| Pre-COVID sales vs. 2020 actual | Be mindful when using new product/services data that could distort comparability, also marketing strategies to retain customers |

| Pre-COVID utilization vs 2020 actual | Economies of scales, cost structures and operating leverage, break-even analysis |

| Exceptional, non-recurring, extraordinary operational cost | Warehousing, logistics, overtime, transport, insurance |

| Government grants, subsidies, programs | Employee retention cost, rental and lease cost, tax waivers, deferral of contributions, interest |

| Macroeconomic data | GDP by country, sector or region, and trade association data can be helpful to confirm Pre-COVID sales vs. 2020 actual conclusions. Macroeconomics analyses might use data such as market share variation and drop in consumption, demand and other market metrics |

| Regressions | Regression analysis of variance analysis is more reliable to

predict variations when a large amount of data inputs are included; thus, it might be of limited help. |

| 2020 Budget vs 2020 real | Budget data is unlikely to be considered official data for controversy or court cases. |

Finally, Guidance made important remarks about comparability adjustments that are likely to be rejected by tax administrations including the following:

Guidance remarks |

Our comments |

| Prior global crisis comparison | Since COVID-19 is an unprecedented crisis like no other, using data from other global crisis, such as the 2008/2009 financial crisis, could lead to poor and superficial conclusions |

| Using Loss-making comparables | Although the Arm’s Length principle does not override the inclusion or exclusion of loss-making comparables[2] as long their inclusion/exclusion satisfy the comparability criteria, extra care should be taken when performing comparability analysis for fiscal 2020 ensuring that chosen comparables assumed similar levels of risk and that have been similarly impacted by the pandemic. |

| Intercompany renegotiations | Related parties that renegotiated certain terms in their existing agreements are advised to identify clear evidence that independent parties in comparable circumstances would have revised their existing agreements or commercial relations, otherwise, such modification of existing intercompany arrangements and/or the commercial relationships of associated parties is deemed to be considered not consistent with the arm’s length principle. Examples of fair renegotiation might include: renegotiate a contract to support the financial survival of any of the transactional counterparties, or to retain key customers, |

| Limited-risk arrangements | Consistency is key to support changes in limited-risk arrangements, for instance, a “limited-risk” distributor did not assume any marketplace risk Pre-COVID and hence was only entitled to a low return, but in 2020 argues that the same distributor assumes some marketplace risk and hence should be allocated losses, is expected to keep bearing such risk in 2021 and so on. |

| Force majeure adjustments | Taxpayers should carefully review existing intercompany arrangements when invoking a force majeure clause to ensure that: i) the arrangement actually includes a written force majeure clause, ii) if no clause existed but one was added in 2020, such clause is also expected to remain in force after the pandemic, iii) the law governing the contract is not a civil law jurisdiction where force majeure would automatically apply, and iv) the specific related party situation actually qualifies as a force majeure. |

As discussed above, reporting the financial periods affected by the pandemic in compliance with the arm’s length principle cannot be done with one single and straightforward approach, in this particular challenge, our preferred approach is to build up from a pre-COVID vs. 2020 actual comparability analysis which in fact compares the actual tested party with itself as long as the pre-COVID pricing policy was not intended to aggressively shift profits within the MNE.

[1] The foundation of transfer pricing is the arm’s length principle, which states that the price, terms and conditions charged in a controlled transaction between two related parties should be the same as that in a transaction between two unrelated parties on the open market. In other words, an arm’s length transaction refers to a business deal in which buyers and sellers act independently without one party influencing the other.

[2] It worth noting that in many cases, domestic legislation and/or tax administration ruling prescribe against the use of loss-making comparable.